VITAL THOUGH it might be, most of us give little thought to the workings of the emergency services. We just assume that should we ever find ourselves in the middle of an emergency situation that once we call 999 the relevant people will arrive to assist.

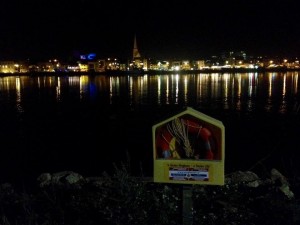

Wexford is a coastal town with a historic ties to the sea. Through leisure and commercial activities our interaction with the sea is continuous.

Approximately 15 times a year Wexford Lifeboat responds to shouts. Similarly, statistics for 2015 indicate that Wexford Marine Watch have dealt with 46 incidents and 27 casualties so far this year.

An integral aspect to the work of these volunteer organisations is the tentative training exercises which they engage in several times a year.

Forging strong working links between the different organisations is a key component of the lifeboat’s new RISE strategy which endeavours to reduce drownings by 50% by 2024.

Members of the RNLI and Wexford MarineWatch gathered at the Wexford Lifeboat Station last Tuesday night for a briefing ahead of a training exercise.

Led by RNLI helm Frank O’Brien and chairman of Wexford MarineWatch Frank Flanagan, the exercise was designed to test the volunteers’ response and knowledge of the relevant protocols, in a simulated rescue.

During the briefing, the group was divided into three groups of four and assigned to different posts to patrol the harbour and bridge area.

It was revealed that a dummy would be thrown into the water at an unannounced location and the volunteers would then have to respond as if it was a real life rescue.

Mr Flanagan told the group that “training is called training for a reason, this is the time to make the mistakes so we can learn from them and not repeat them during a real incident”.

And training is never a straight forward exercise, as the volunteers were about to discover.

After approximately twenty minutes into the patrol, the dummy which for the purposes of training has been named Fred, was thrown into the water at the end of the marina arm.

The volunteers responded swiftly and used a search light and red flare to track the movement of the casualty in the water while they went through the motions of putting an emergency call into the Coast Guard, National Marine Rescue Centre.

Mimicking the estimated response time of the lifeboat, which is between six and eight minutes, the lifeboat crew waited this length of time before arriving at the scene and recovering the casualty.

However, while the Wexford MarineWatch volunteers were dealing with this incident another call came through over the emergency channel on the radio alerting them to second incident which was unfolding “at the end of the marina arm”.

The volunteers were uncertain for a couple of moments of what this call meant as the volunteers were of the opinion that they were already standing at the end of the marina arm.

As Peter Scallan of the RNLI explained, this demonstrated to the volunteers that awareness of the location and dealing with “imperfect information” from members of the public is a key part of the work involved in a rescue.

It transpired that the organisers had planted an actor at the opposite end of the marina arm. This man pretended that he was attempting to take his own life and the volunteers were forced to intervene and encourage him to move away from the rocks.

The volunteers were unsure whether the situation was a real life suicide attempt and the group were forced to deal with this situation and the recovery of the casualty from the water simultaneously.

“This was purposely done to show the volunteers that while one incident is unfolding you have to be conscious of other incidents that may arise,” said Peter Scallan.

Mr Scallan gave the example of a dog drowning and a member of the public entering the water to save the animal. “You might be dealing with one accident and focussing on that and not realise that another person has gone into the water at a different location.”

He continued: “This is the kind of stuff which comes up in a real shout. We are up to a little bit of skulduggery here tonight throwing in a second incident for them to deal with, but we are trying to incorporate everything into the training exercises.”

This scenario also highlighted the importance of giving as much information as possible about the casualty such as the gender.

After the first exercise was stood down, the volunteers re-grouped at their different locations.

The second exercise was kick-started when Peter Scallan took on the role of a member of the public and came running over to a group of Marinewatch volunteers shouting that he had heard a splash and thought that someone had entered the water at the Ferrybank side of the harbour.

Reacting at speed the group began to look for the casualty using search lights.

Once they had located the dummy in the water they tracked its movement using search lights and red flares which pinpointed its location and identified it to the lifeboat crew which arrived on the scene.

Within three minutes of entering the water the casualty had floated out beyond the sea wall.

This showed the group the speed at which a casualty can be dragged out to sea by the tide, which was at this point moving in an outbound motion.

The sea wall is an obstacle for the lifeboat crew. There is one break in the wall which is enough to allow the boat pass through, but it frequently causes damage to the propeller.

Given that this was a training exercise helm Frank O’Brien decided to travel out around the wall, a distance of three quarters of a mile, in order to reach the casualty rather than risk damage to the lifeboat.

“Obviously if this was a real-life rescue we would have gone straight through, but we didn’t want to risk damage to the boat during a training exercise,” Mr O’Brien said.

The lifeboat travels at a speed of 25 knots, which is the equivalent of 45 km/hr.

The final training exercise of the night proved to be the most difficult.

Two objects were thrown into the water, one was a cabbage meanwhile the second was the dummy.

The description given for the first casualty was “a person wearing a green hat” which prompted the safety patrol unit to respond to visuals of a green object floating inside the marina near to the trawlers.

Meanwhile, patrols on the bridge tracked the dummy which entered the water at the Crosstown side of Wexford bridge, but swiftly moved out of the harbour in the direction of Maudlintown.

The volunteers identified the casualty in the water rapidly and followed the necessary protocols to track it with the use of the search light and red flare until the lifeboat reached its location.

The group moved quickly to keep up with the casualty which floated quickly out of the harbour and after it was determined that the cabbage planted in the marina was a false alarm, the patrols on that side of the harbour moved over to offer assistance also.

However the group neglected to throw a lifebuoy to the casualty as it passed under the bridge. A lifebuoy would have more than likely moved in the same direction as the casualty and the reflectors on it would have been visible to the lifeboat crew.

Visual contact of the dummy was temporarily lost during the exercise, but it was recovered a short while later.

After the training session was stood down all volunteers returned to the lifeboat station and during the de-brief it was stressed that the mistake made in forgetting to throw the lifebuoy to the casualty was one of the key reasons that the casualty had not been recovered quicker.

The volunteer who had been maintaining a visual on the casualty also noted that he had turned momentarily to say something to another volunteer and in that split second he had lost sight of the casualty.

Chairman of Wexford MarineWatch stressed that this training exercise had been invaluable to his members, because it had shown them the importance of following the key protocols that are outlined to its members to follow in a rescue operation.

“It’s about learning from practice,” said Mr Flanagan.

He continued: “I think the success of Wexford MarineWatch is partly due to the strong relationship that has been forged over the past three years between ourselves and the crew of Wexford Lifeboat. Training is regular, varied and realistic – this exercise was evidence of exactly how much each organisation relies on the other in a real-life scenario.”

Life-saving tips for the public

•If you are calling 999 for a rescue in or near water or a mountainous region always specify that you need the coast guard. Don’t ask for the guards, ambulance service or fire service the coast guard is the appropriate emergency service to deal with an incident of this nature. Once the coast guard is alerted, it has a number of resources at its disposal that it can deploy. These include the RNLI, the Civil Defence and the Rescue 117 helicopter.

•When you call 999 state your location in a loud and clear voice before you give anymore details. Your location is the most important information. It tells the operator where you are and as soon as your location is revealed the operator will press a button to launch the relevant rescue service in your area. More often than not the closest rescue service will be deployed by the touch of a button before you have even hung up the phone.

•When giving details of your location be as precise as possible. Identify landmarks that are visible to you. For instance if a casualty enters the water off the quay front, identify the nearest shops or the colour of the closest trawler to you. A common misconception encountered by the emergency services is when members of the public confuse Wexford Harbour and Wexford Bay. Wexford Harbour describes the area at the quay front, meanwhile the sea area out from Curracloe is Wexford Bay.

•If you witness a casualty in the water keep your eye on him/her. Don’t look away. Ask somebody else to call 999. If you look away even for a split second you might lose sight of the casualty and it is extremely difficult to re-locate the person. The tide can move a casualty at a speed of a metre and a half per second.

•Don’t ever jump in after the casualty. The rescue services in Wexford have one of the fastest response times in the country and will arrive on the scene as swiftly as possible. They are the best equipped to deal with a casualty. If you enter the water also, it is possible that you too will get into difficulty and need to be rescued also. This means that the rescue service will be forced to deal with to rescue operations rather than one.

•Throw a lifebuoy into the casualty. Even if they are unable to grab hold of it, it will move follow the direction that the casualty moves in the water. Throw any other objects you can find in after the casualty so you are essentially littering the water with items that will float nearby the casualty. Objects such as a cushion from your car, an empty petrol can a puffa jacket are all useful for this. Ensure that the person who has a visual on the casualty does not run to fetch these items. Shout for help and have someone else do so.

•Don’t shine your car lights on the casualty to alert the lifeboat to the location unless you are instructed to do so by a member of the emergency services. Members of the public often think that this helps, but bright lights can dazzle and cause a loss of night vision. It can take an individual up to 30 minutes to recover their night vision in this situation.

Have you got what it takes to become a volunteer?

Wexford MarineWatch is currently recruiting new volunteers. Established in December 2012, its primary objective was to try and reduce the high level of death by suicide in the Wexford Harbour and Bridge area.

Wexford MarineWatch now has in excess of 80 volunteers who give their time on a rota-basis each month to help prevent loss of life, make people aware of the dangers of the water and provide assistance to anyone who may be in difficulty.

They also monitor life-saving equipment in the area ensuring all are in tact and functioning correctly, whilst replacing any damaged or vandalised items such as stolen ringbuoys or tangled ropes.

Each team of volunteers is headed up by a Supervisor, who is responsible for liaising with the Emergency Services including the Irish Coast Guard, RNLI and the Gardai at regular intervals. All Volunteers are trained to a high standard, some which is overseen by the RNLI – and regularly carry out exercises with the other Emergency Services.

The primary purpose of the scheme is to provide an “Suicide Intervention” – to identify and intercept people who may be in difficulty before they harm themselves – and alert the correct emergency services accordingly. Our secondary remit is general ‘Water Safety’ and our teams have even prevented numerous drunk revellers from uncertain death in the early hours (unknown to themselves the following morning), who have staggered too close to the edge of the open Quays or put themselves in danger. Not every death in the harbour is suicide – a high percentage have also been accidental.

Whilst the volunteers interact with persons in distress, they do not enter the water.

They are there to provide a distraction and offer support (while the appropriate emergency services such as the RNLI and Gardai are summoned by colleagues), along with lending a listening ear and providing the person with information on local 24 hour professional assistance that is available, which they may not be aware of.

If you are interested in becoming a volunteer email [email protected] or download the application form directly from the organisation’s website www.wexfordmarinewatch.com/volunteering

All the details of where to post the form are there also.