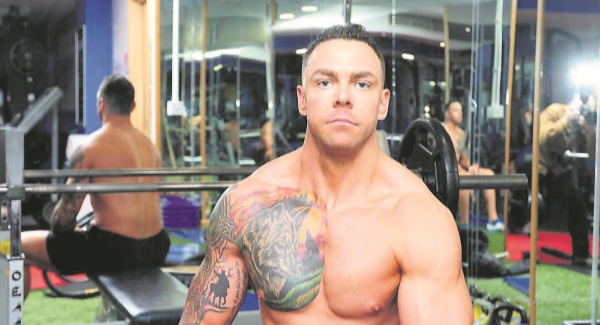

When PJ Ward steps out on stage in nothing but his underwear in Kilkenny tomorrow, he’ll do it for his sanity, not vanity Writes Jackie Cahill.

He’ll be emotional, and the reasons why are not difficult to understand. Ward has finally found some peace after a traumatic five years.

The Republic of Ireland BodyBuilding Federation event at The Hub may not bring Ward a medal but it will bring the curtain down on the most painful period of his life.

Last Saturday marked the fifth anniversary of an episode that turned his entire world upside down.

April 23, 2011, the day after Good Friday, was a bad Saturday for the man who played senior football for Offaly, Westmeath and New York during his career.

After returning home from the US in August 2005, Ward looked for a job with security and a pension.

He decided to become a prison officer and was thoroughly enjoying his professional career.

That was until the fateful day in Mountjoy when, during the course of his duties, he and a colleague were assaulted. Ward was located in the notorious B Base of Mountjoy when prisoners singled out Ward before another prison officer intervened.

Hopelessly outnumbered, all the pair could do was assume the foetal position and wait until help came.

Ward hit the alarm on his radio but it took several minutes for fellow officers to respond.

As Ward waited for assistance to arrive, he suffered a sustained, vicious attack from his assailants.

He was left with serious chest and shoulder injuries, requiring surgery in October 2011, but the biggest fallout was psychological.

A few weeks after the Mountjoy incident, Dr John Lunn at the Hermitage Medical Centre in Dublin told Ward football was no longer an option, at any level.

“I could be hit by a bus now and nothing might happen,” Ward explains.

“But the young lad could push me up against a wall and it’s lights out. I have to be careful going about my daily business, in case I get a belt in the chest.

“I can’t get myself into a situation where I could be hit in the chest or shoulders. Anything with physical contact is out the window.”

PJ Ward’s body-building regime has been modified to take into account the damage inflicted on his right shoulder.

He still doesn’t have full mobility and that area of his body is now decorated with tattoos, his bicep and tricep bearing the words of a Biblical passage from Corinthians, Chapter 10.

“No trial has come to you but what is human. God is faithful and will not let you be tried beyond your strength; but with the trial he will also provide a way out, so that you may be able to bear it.”

There’s the number 14 to symbolise the number he wore as a Gaelic footballer, a shamrock representing the clubs in Offaly and Westmeath that he played for, stars with the letters A, O in the middle, the initials of his sons Aodhán and Odhrán, and a love heart with the letter S for his wife Sinead.

“I would have my own extreme, strong faith,” Ward says. “I won’t say I’m a preacher or I go to Mass every week but I have strong faith in God and I know God has helped me through the difficult times.”

There’s another tattoo of a Celtic warrior, the reason being that while there were times over the last five years when Ward tried to give up, he still maintained a semblance of belief he could make it through.

“My fight will hopefully end on Saturday,” he whispers. For anybody that’s never previously suffered a panic attack, it’s a frightening experience.

It was the end of May 2011, a month after Ward was attacked, and he’d been sitting at home for a couple of weeks, incapacitated.

“Like everything else, you get bored, extremely bored,” he remembers.

“I can remember it as plain as anything. It was a Thursday and I was in the kitchen. All of a sudden, my heart started to pound and I started to sweat extremely heavy. I found the room had closed in on top of me and I was backed into a corner, down on my hunkers and I didn’t know what was going on. That was the start of my issues right there.”

He began to experience panic attacks up to four times a day and a man who had it all began to feel like he had lost everything.

A non-drinker and non-smoker, GAA was Ward’s social outlet, his only one.

“All of a sudden that’s gone, you’re at home and you don’t know what the story is with your job.

“You’re beginning to struggle financially because you’re off sick and trying to figure out your next move.

“Then the panic attacks came and you don’t understand those and I found myself constantly thinking about the situations I was in.

“What happened in that incident in work then started to play on my social life and my home life.” PJ and Sinead were married in September 2010 but within seven months they were faced with this most unexpected of obstacles.

Ward became a virtual prisoner in his own home and wouldn’t leave the house even though his parents lived just 500 yards up the road.

Whenever the doorbell rang he was on high alert, ready to pounce, in attack mode.

“My awareness was massively heightened, I became extremely vigilant and nothing would pass the road that I didn’t know about,” he says.

“This continued and it started affecting my sleeping. I wasn’t sleeping. It came to a stage where I was so worn out I fell asleep, but then the nightmares started.” Sinead informed PJ he had started to shout and scream in his sleep. One night, she rolled around to place a protective arm around her husband when, still asleep, PJ pinned her by the neck to the headboard of the bed.

“At that point I woke up,” he recalls. “I asked her what was after happening. I didn’t know what I was after doing. She explained to me and that was the real key point. I knew there was something more going on than just the worries of not working and so forth.” In the weeks that followed, Ward’s mood darkened and he made a visit to a GP.

“The usual thing, get your bag of pills, SSRIs or whatever they’re called, and I was sent for therapy.” He was diagnosed with Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and depression.

Tough to take for “ a fella who had been extremely lucky in life prior to that.”

Ward enjoyed a successful football career, may not have won All-Irelands or All Stars but still played at a high level and ran out at Croke Park.

He had a beautiful wife and a great job but had now ballooned from his ideal football weight of 14 stone 7lbs to over 19 stone.

He’d stay in bed for days and not eat, before staying in bed for days eating whatever he could get his hands on.

His parents had to look after the kids during the day because he wasn’t fit to look after them, and he was sitting on the edge of the bed at night with a baseball bat by his side.

“It came to a stage where my GP said this is gone way too serious,” Ward says.

“Myself and my wife were due to go away for a night together, to Kilkenny, but things just got so bad that my GP said no.”

Ward was sent to St Loman’s in Mullingar, a psychiatric hospital, and he remembers driving in with Sinead and crying in the car, wondering how his life had come to this.

He was kept overnight but for no longer. “I had a foreign guy and he couldn’t understand what I was trying to explain to him. The next day they left me out and I was referred to another psychiatrist but my therapy was slow.” Ward tried ‘exposure work’, which required him to sit down and write about his assault.

“Every time I tried to do this, my mood slipped even more and the depression got worse.” Towards the end of 2014, he changed from a psychiatrist to a psychologist in Athlone, John Donohoe, and that’s when things began to change for the better.

He’d tried exercise again during the bad times, cycling with friends and lifting some weights, but that might last for only two or three days and he “wouldn’t look at the gym again for four or five weeks.” Ward needed a challenge and he spoke to a GP, Gerry O’Flynn in Kilbeggan.

They began talking about outlets and what Ward could do. He got in touch with the Gaelic Players Association and they provided massive support, covering his psychology bills as Ward signed up to an online strength and conditioning course with Setanta College.

He’s roughly halfway through that now and looks after the Offaly U16 footballers while also working with Clodiagh Gaels, a new club which contested a county intermediate hurling final last year.

Aware that the ‘one size fits all’ approach doesn’t work, he screened each player, assessed their movement and designed individually, tailored programmes.

It also helps that a number of the players work out in the gym at the Bridge House in Tullamore, a second home for Ward since he decided last year that he wanted to enter a bodybuilding event.

His process for tomorrow’s competition, and Mr. Cork on May 15, began last May, when his weight was 19 stone 4lbs and he was carrying 29% body fat.

He is now 15 stone and boasting just 8% body fat ahead of Kilkenny, training three and a half hours a day and when we meet he is eating a post-workout meal comprised of 80g porridge oats, mixed with two scoops of whey protein, and salt.

He’s now a fully-sponsored RAW Powders athlete but surviving on illness benefit while also volunteering his services to local sports teams.

Life is good but his training is extreme and there are still days that leave him feeling broken.

“Last Friday week, I could have thrown in the towel down there,” Ward says.

“With physical training, you’ll get through it and I would because of the GAA background, with the history of someone telling you to run through muck and shit every night of the week.

“It’s the emotional and mental stress it puts on you. I was stood down there on Friday, doing my chest and feeling so physically tired and drained.

“I was stood over the barbell and tears welled up in my eyes. I felt like I didn’t have the physical energy to do it but then I thought, ‘why come so far to give up at this stage?’ “You find energy and that little bit of drive, something I didn’t have in the last five years.

“I’d completely lost myself. When I was playing football, if you asked me to climb a roof, I would have climbed it. But with depression and PTSD, you lose all of that. No faith, no confidence, no road, no path for where you want to go.”

Bodybuilding has helped to save PJ Ward’s life.

When he decided to commit fully to it, a big factor was his personal vow that what happened to him in Mountjoy would never happen to him again.

He’d always had an interest in bodybuilding and now had the time to immerse himself fully in the discipline.

He remembers his 13th or 14th birthday, a trip to Dublin and the memory of his Dad carrying a set of dumbbells around Capel Street.

“All I was doing in my bedroom was a few bicep curls and sit-ups to get a six-pack and a set of arms,” Ward smiled.

“You had the magazines and you wanted the six pack.

“But I needed something that was going to give me prolonged stability. I needed to challenge my mind again, and my body. If I was looking for something short-term, it wasn’t going to work.”

It’s given him structure again and he planned his 30-week schedule like a GAA season.

The really serious training began last September and he’s taken useful advice from Brian Hickey, a National Amateur BodyBuilders’ Association (NABBA) legend.

Hickey is also studying at Setanta College, for a Masters degree in nutrition, and Ward has drawn from his experience.

“I said to Brian, ‘I need this, I’m signing up for this’ and he put me on the right track.

“The short-term goal was to get to Christmas and see where it went from there.

“That would leave us 16 weeks from competition and we hit all of our targets at Christmas.

The early part of this week saw Ward depleting his body of carbohydrates and drinking ten litres of water a day.

He’s cut that down to two litres a day now and when he restores carbohydrates, he’ll hit the scales around the 15 stone 3 or 4 lbs mark.

The fact that it’s Kilkenny, where he and Sinead were meant to spend that night away, makes it even more special.

And it’s close to that five-year Mountjoy anniversary, too.

“I just feel it has that whole connection and this is the process of the whole new me,” Ward says.

“Where I was, this time 18 months ago, when things started to get a little bit better with the help of John Donohoe, to where I am now, has been a journey and I hope Saturday brings closure to what we’ve been through over the last five years.

This story first appeared on the Irish Examiner